Walter Behrens

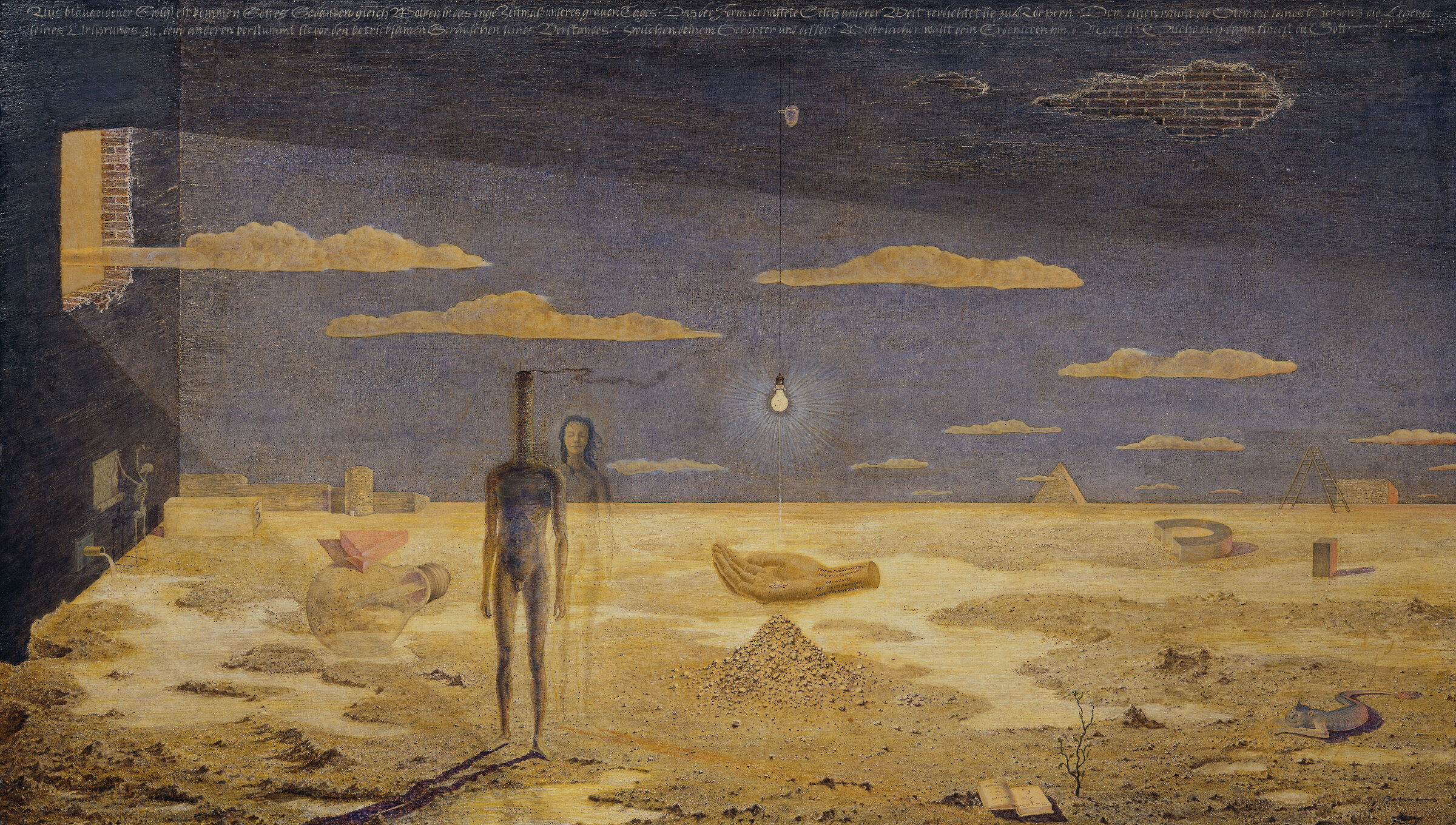

Walter Behrens, Verstand und Gefühl (Ewigkeit und Zeit), 1947 – 48

Oil on fiberboard

39.4 x 67 cm, frame: 50.5 x 78.5 x 5 cm

Courtesy Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna, Photo: Belvedere, Vienna

As the son of German parents, Walter Behrens joined his fellow Austrian artists relatively late. He first studied at the Hamburg School of Applied Arts, and then, after his military service during the war, he did two further semesters at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts in the class of Carl Fahringer. Behrens joined the Art Club, from which the Vienna school of Fantastic Realism emerged, although the group’s name was only coined some years later.

Behrens’s work is very typical of the Fantastic Realism movement, and he is often named as a founder member of the group, but nonetheless his works were not included in the group’s major exhibitions and he remained somewhat detached from their international success.

In Verstand und Gefühl (Ewigkeit und Zeit) (Intellect and Emotion [Eternity and Time]) (1947 – 48) we gaze from the front into an interior space characterized by a floor, walls, and a window. This room looks like a desert landscape by night. The walls are like a sky with a few clouds, while the perspective is slightly distorted by one of the clouds seeming to come into the room through the window. The overall impression is of an interior stage set, with peeling plasterwork in the background at the top right and a piece of wall on one side of the window. Beneath the window there is also an electricity socket that takes us to a second intriguing and also humorous aspect of this picture. On the one hand natural light enters through the window, while on the other the room is illuminated by a light bulb handing from the ceiling on a cable right in the middle of the image. Natural and the artificial strangely cohabit here.

The work of Behrens certainly seems to display strong influence from the compositions of international surrealism, above all Max Ernst and Salvador Dali. And yet a closer look shows that most aspects of Behrens’s works are different, and executed in far more detail. In the work on show here, this can be noted in the very precise depiction of the rubble and the desert ground.

The theme of time, or eternity as its theoretical counterpart, can also be seen in Dali’s iconic works. But Behrens places this theme much closer to Christian iconography and the topos of paradise. We see two semi-transparent human figures, like a bizarre depiction of Adam and Eve, even if the man’s head is replaced by a smoking chimney top, and also a notable line of text at the top of the picture. This can all be seen as a complex reference to the history of painting and its long Christian tradition. While Dali’s work is based on insights of modern science such as Einstein’s theory of relativity and the phantasms that this can reflect, the sphere of reference for Behrens is rather artists like Hieronymus Bosch, Giuseppe Arcimboldo, and Peter Paul Rubens. Here one can agree with the art critic Johann Muschik, who coined the term Fantastic Realism, when he said that “Fantastic painting in Austria has very old roots.”1 Muschik’s line of thought leading to an independent and regionally specific fantastic genre followed a series of steps from the Danube style with the transition from late Gothic to the Renaissance, and then via the Baroque and Romanticism up to his own present day.

- Johann Muschik, Die Wiener Schule des Phantastischen Realismus, Vienna 1974, p. 57.